|

With the exception of the Venus tables of Ammiza-duga, which probably originated in the seventeenth century BC, most of the surviving Mesopotamian astronomical texts were written between 650 and 50 BC. These clay tablets with cuneiform writing are called astronomical diaries, and they are the unmistakable observations of specialists: professional astronomer-scribes. A typical diary entry begins with a statement on the length of the previous month. It might have been 29 or 30 days. Then, the present month's first observation - the time between sunset and moonset on the day of the first waxing crescent - is given, followed by similar information on the times between moonsets and sunrises and between moonrises and sunsets, at full moon. At the end of the month, the interval between the rising of the last waning crescent moon and sunrise is recorded. When a lunar or solar eclipse took place, its date, time, and duration were noted along with the planets visible, the star that was culminating, and the prevailing wind at the time of the eclipse. Significant points in the various planetary cycles were all tabulated, and the dates of the solstices, equinoxes, and significant appearances of Sirius were provided. The Babylonian astronomers used a set of 30 stars as references for celestial position, and their astronomical diaries detailed the locations of the moon and planets with respect to the stars. Reports of bad weather or unusual atmospheric phenomena - like rainbows and haloes - found their way into the diaries, too. Finally, various events of local importance (fires, thefts, and conquests), the amount of rise or fall in the river at Babylon, and the quantity of various commodities that could be purchased for one silver shekel filled out the diligent astronomer's report. By the sixth century BC, Neo-Babylonian astronomers were computing in advance the expected time intervals between moonrise or moonset and sunrise or sunset for various days in the months ahead. These calculations were based on systematic observations. Later, when combined with numerical tabulations of the monthly movement of the sun, the position of sun and moon at new moon, the length of daylight, half the length of night, an eclipse warning index, the rate of the moon's daily motion through the stars, and other related information, these computations enabled reasonably detailed and accurate predictions of what the moon would do and when it would do it.

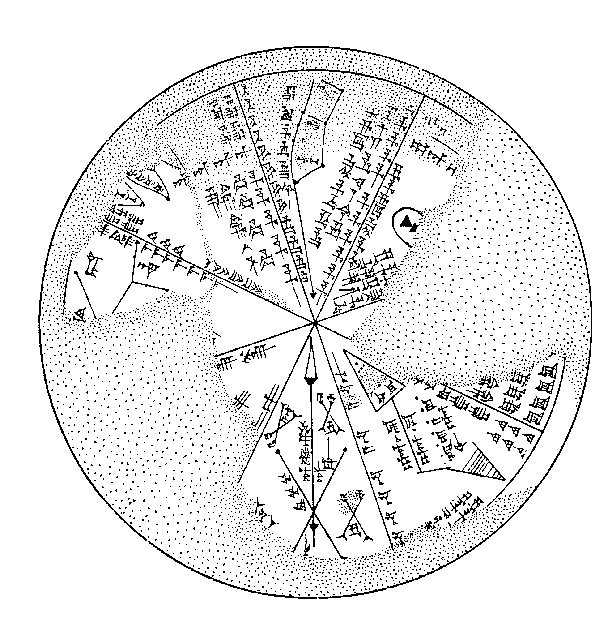

Assyrian star map from Nineveh (K 8538). Counterclockwise from bottom: Sirius (Arrow), Pegasus + Andromeda (Field + Plough), [Aries], the Pleiades, Gemini, Hydra + Corvus + Virgo, Libra. Drawing by L.W.King with corrections by J.Koch. Neue Untersuchungen zur Topographie des Babilonischen Fixsternhimmels (Wiesbaden 1989), p. 56ff.

Of course, the Babylonians never developed completely accurate representations of nonuniform motion, but in the later dynasties of Mesopotamia, and especially in the Seleucid period (301-164 BC) following the death of Alexander the Great, Babylonian (during this period called Chaldean) astronomers approximated the cyclical accelerations and decelerations of the moon and planets with the "zigzag functions." They did this numerically, not graphically, but the technique worked well enough for their purposes. Despite the extensive written record of Babylonian astronomy, we have very little knowledge of the instruments used in ancient Mesopotamia, and we know even less about the observatories which must have existed. A clay "astrolabe" from Assyria is on display in the British Museum in London. Actually, a true astrolabe is used to measure the angular height of a celestial object, and the Assyrian devices look more like diagrams of the zones of the sky. They seem to be tables of handy astronomical information, designed to guide the astronomer in keeping time. Apart from a few limited references to an instrument used for measuring transits, the gnomon (or shadow stick), and the water clock, this is the complete inventory of our knowledge of Babylonian astronomical instruments. It should not surprise us, however, that the astronomical instruments and observatories of ancient civilizations are hard to find. It is unlikely there were many of them, and the observatories that still exist may be hard to recognize for what they are. The actual equipment probably disappeared long ago, and the walls that housed the ancient astronomers may be all that remains today. If such observatories were incorporated into temples or palaces, they might be even harder to recognize. When we find a structure with astronomical alignments, it is not always easy to tell if the structure was used ritually or for actual observation or both. A perusal of nearly any ancient pantheon reveals the obvious: At least some of the gods, often the most important ones, are objects in the sky. The metaphoric reasons are not difficult to understand. The regular motions of celestial objects made them agents of order that helped give meaning to the world below; endless repetition of their appearances and disappearances suggested immortality; their light commanded attention and connoted power. And being in the sky, with such a perspective on earth below, it was only natural to assume that the gods must know all because they could see all: To see the world, one's eyes must be in heaven. Although particular gods may differ in terms of the resources they are believed to control, control is the attribute they share. What they control, and how they do it, determines exactly what sorts of gods they are. Celestial gods control the passage of time by marking it and measuring it. They control direction and space through the locations of their comings and goings. As masters of time and space, they move the world. They make it change. Day changes into night. Winter melts into spring. Rivers flood and fall. Grain sprouts, grows, and ripens. In these cycles of the world and in our daily lives we see patterened change, and it is driven by the sky. If we are seeking immortality,

the sky is a good place to start. We see endless repetition

there. Although we know that we ourselves will die, we see the

sun, moon, and stars survive night after night, month after

month, year after year. They may disappear, but their absences

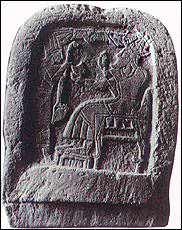

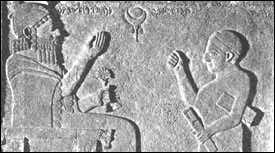

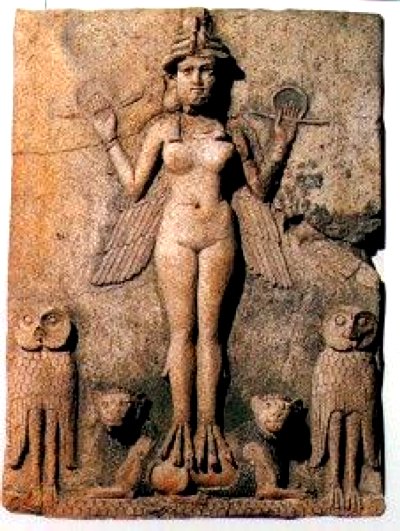

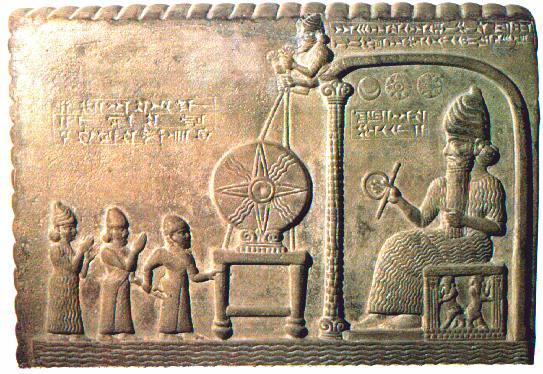

are only temporary. The power of the celestial gods was revealed by their light. Anyone standing in sunlight senses its energy. Its warmth is unmistakable. Though obviously weaker, the moon and planets also command respect. They shine not only in the blackened vault of night but, on occasion, in the brighter twilight sky, and some can even be seen in broad daylight. Again and again, gods were associated with light. For example, Any, or An, was the greatest of the Sumerian gods. His name was the word for "sky" and "high," and the written symbol for his name was shared with the word diugir: "shining". Equal reverence for the softer, indirect light of the moon is evident from a text from Ur, in the Mesopotamia of the third millenium BC: "Nanna, great lord, light shining in the clear skies, wearing on his head a prince's headdress right god for bringing forth day and night, establishing the month bringing the year to completion." Another Sumerian prayer invokes the brilliance of Inanna, the goddess Venus, in the evening twilight: "The pure torch that flares in the sky, the heavenly light shining bright like the day, the great queen of heaven, Inanna, I will hail ... Of her majesty, of her greatness, of her exceeding dignity of her brilliant coming forth in the evening sky of her flaring in the sky - a pure torch - of her standing in the sky like the sun and the moon, known by all lands from south to north of the greatness of the holy one of heaven to the lady I will sing." The particular appearance and behavior of certain celestial objects have often led different peoples in different places at different times to assign the same symbolic values to them. The sun, for example, is both powerful and dependable, as it pursues its orderly course through the seasons, and these characteristics have inspired many peoples to see in it the source of all authority, law, and social order. In ancient Babylon, the sun was Shamash. His watchful eye noted all things and judged everyone. Justice resided in him. Hammurabi, the great codifier of Babylonian law, is shown standing before Shamash on the stone column, or stela, inscribed with this king's famous Code. Through law the sun's order was transferred to earth. Compared to the sun, the moon's

rapid changes make it seem practically vagrant, but it is useful

as a timekeeper, and many people have accorded it divine status

as such.

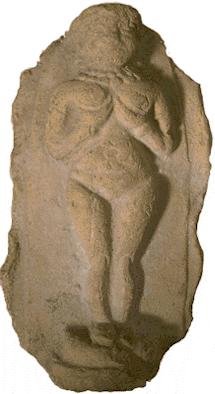

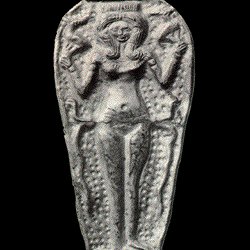

In ancient Babylon, Marduk was honored as king of the gods and quite specifically associated with the planet Jupiter. In Greece, Zeus was chief of the Olympians, with dominion over the planet Jupiter. In that sense he was the counterpart of Marduk. By contrast, the Egyptians portrayed Jupiter - and Mars and Saturn as well - with the falcon head of the skygod Horus. The role of Jupiter-Marduk was preeminent in Babylon, for he was credited with the world's creation, bringing order out of chaos. Texts of the Babylonian creation myth are preserved on cuneiform tablets, some from the library of Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria in the seventh century BC, but the tale itself is much older, apparently deriving from the Old Babylonian empire, about 1800 BC. In the myth, Marduk establishes order by killing Tiamat, the dragon of primordial chaos. From the monster's body he fashions the sky and the sea. Then he prepares to take advantage of his victory. His price for his service is the right to fashion an ordered cosmos. First, he organizes the sky, apportioning it among the other gods, symbolized in the constellations overhead. The year is next. Marduk decides how long it will be and subdivides it into months, their passage regulated by the stars he chooses. More celestial references, contrived by Marduk, put the world in order. He also marks the horizon, the zenith, and the points where the sun might emerge and depart. He puts up the moon and assigns it to light the night and count the days of the month. Clearly Marduk was the ruler of the sky. Jupiter's course through the sky, Marduk decides, will guide the stars and planets. This may seem like an odd choice to make. The constant sun, perhaps, would define things better. But Jupiter's path through the sky follows the ecliptic, the annual path of the sun, more closely than the other planets known to the ancients. Also, Jupiter's configurations in the stars repeat themselves almost exactly every 12 years. For example, Jupiter will come into opposition (that is, be opposite the sun in the sky) 12 times in a span of time just five days longer than 12 years, and the last opposition will occur among the same stars as the first. These aspects of Jupiter's movement, combined with its brilliance among the stars of the nighttime sky, probably influenced early astronomers to use the planet as a reference, a function reflected, it seems, in the myth. There are uncertainties, however. The actual name for the planet used in the text is Nebiru. Although this did mean Jupiter, it meant other things as well, and sometimes it meant pole, or pivot. The north celestial pole is a key reference for the sky's rotation, so either or both meanings may have been intended in the creation epic. The other planets also played important, often similar, roles in the pantheons of ancient cultures. And so, the Babylonians associated Ishtar, their goddess of love and fertility, with the planet Venus, another parallel- and perhaps direct antecedent - to Greek and, ultimately, Roman tradition. Apart from its brightness, the most distinctive feature of Venus is its cycle as a morning star and evening star. Accordingly, the Egyptians symbolized Venus as the Bennu, a heron-like bird commonly equated with the phoenix.

The Bennu belonged to Osiris, probably because the Egyptians associated death and resurrection with the planet's evening and morning appearances, or perhaps with its conjunctions behind the sun and its periods of visibility. Something similar may be behind the Mesopotamian myth of Ishtar's descent into the Underworld.

Among the Babylonians, Mercury was Nebo, the record keeper and messenger of the gods. Its status as messenger may be related to the quickness of the planet in its circuit from west of the sun to east of the sun and back to the west again. Mercury's swiftness also made him the gods' messenger in Greece and Rome, as well as the escort of the souls to the realm of the dead. It is easy to pick out Mars in the nighttime sky. Its red color sets it apart from the other planets and from most of the stars. The color -the same as blood - also explains its association with gods of war: Nergalin Babylonia, Ares in Greece, and, of course, the Roman Mars. Finally, Saturn, the last of ancient "wandering stars," was known as Ninib to the Babylonians. After an initial career as a sun god and patron of the ancient city of Nippur, Ninib became affiliated with springtime and planting. By observing what transpired

overhead, shamans and astronomer-priests fashioned calendars

and scheduled ceremonies. They had access to the domain of the

gods and the source of cosmic order; this allowed them access

to "knowledge" of the state of the cosmos. They could,

then, communicate the celestial signs of the gods' intent to

earth. Calendric divination made soothsayers, for example, out

of the ancient Mesopotamian moonwatchers. In 1900, Assyriologist

R. Campbell Thompson compiled hundreds of astronomical omens

into a book with the engaging title "The Reports of The

Magicians and Astrologers of Nineveh and Babylon." Many

of the reports involve the moon:

In Mesopotamia it was probably

the Sumerians, the people who built the formative civilization

of the region, who put the first formal calendar into use. The

Sumerian calendar was lunar, but its months began when the first

crescent was sighted in the west. A passage in the Babylonian

creation myth echoes, in Marduk's instructions to the moon,

a concern for the lunarcycle: The "crown" is the

moon's fully lit disk, and the horns refer, of course, to the

waxing crescent. On the seventh day a "half crown"

describes the half-lit first quarter moon, and the rest of the

text narrates the way in which the moon should continue to measure

out the months. In Chaldean times, a "Metonic",

or

19-year cycle with 7 extra months, was probably in use. No matter what method was used

to keep the Mesopotamian lunar calendar coordinated with the

seasons, only the king could declare when an extra month was

to be inserted.

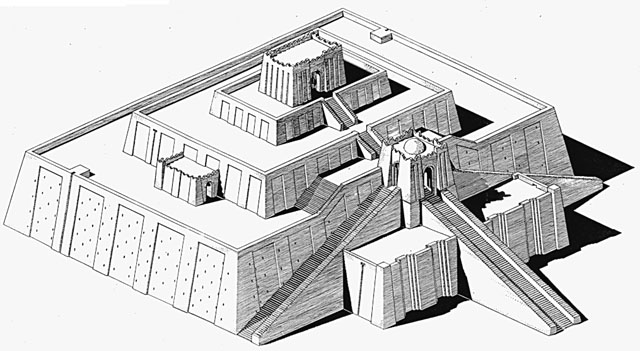

It is possible that this

part of the ceremony was connected in some way with the ziggurat.

On the fourth day of the akitu, the Enuma elish was repeated,

and this activity, accompanied perhaps by others, brought Marduk

back to life and allowed him to "emerge" from the

Mountain, or the underworld. We have already seen how such metaphors

equate with sunrise and with the start of the New Year.

More prayers and rituals continued the New Year ceremony, which lasted for 11 days. A ritual called "fixing of the destinies" and clearly involved with omen readings for the coming year took place.

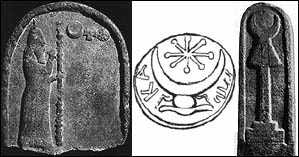

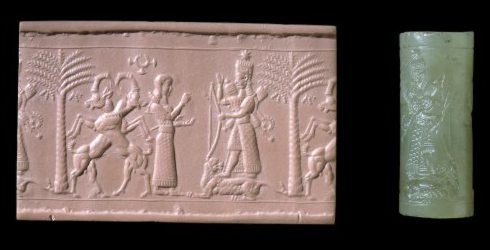

Because some astronomical objects

move through the sky in repeated and known intervals of time,

the behavior of the celestial gods associated with them can

be symbolized numerically. Ishtar, as the planet Venus, perhaps

was handled this way in the eight-pointed star that usually

stands for her on Babylonian boundary stones.

After an appropriate description of the land in question and a list of those involved in effecting the transaction, the boundary stone of King Marduk-ahe-erba forcefully counsels, "Whenever ... any one

shall arise and against that field shall raise a claim or cause a claim to be raised,

shall say the field is not the gift of the king and shall order

a thoughtless man, a fool, a

deaf man to approach that inscribed stone and shall throw it into the water,

burn it with fire, hide it in a field where it cannot

be seen. May the great gods, as many as

on this stone by their names are mentioned with an evil curse, that is without

escape, curse him. May Anu, Enlil, and Ea

in anger look upon him and destroy his life, [and] the children,

his seed. May Marduk (Jupiter), the lord of constructions

(?), stop up his rivers, and Zarpanitum ( ), the great mistress,

spoil his plans. May Ninib (Saturn) and Gula ( ), the lords

of the boundary and of this boundary stone,

cause a destructive sickness

to be in his body, so that, as long

as he lives, he may pass dark and bright red

blood as water. May Sin (Moon), the eye of heaven and

earth, cause leprosy to be in his body, so

that in the enclosure of his city

he may not lie. May the gods, all of them, as

many as are mentioned by their names, not grant him

life for a single day." Not all of the identities of

the gods named and symbolized on kudurru are known, but most

(and perhaps all) of them are celestial. Three prominent symbols

included on most stones refer unambiguously to Shamash, the

sun; Sin, the moon; and Ishtar, the planet Venus. 3 Very direct symbolism in the

signs for the sun and the moon and in several other symbols

whose meaning is understood tempt a guess that the symbolism

in the Star of Ishtar (Venus) is in some way equally direct. Perhaps

the number eight is itself symbolic, for Venus experiences an

eight-year cycle. During that time it passes through its complete

evening star/morning star/evening star pattern five times. This

means that a configuration of Venus recurs on the same calendar

date after eight years, which is how long five complete back-and-forth

passes to either side of the sun take. "If on the 25th of Tammuz Venus

disappeared in the west, for 7 days remaining absent in the sky,

and on the 2nd of Ab Venus was seen in the east, there will be

rains in the land; desolation will be wrought. (year8) " Apart from a few exceptions,

an eight-pointed star is used exclusively for Venus on the Kassite

boundary stones. Bibliography: E. C. Krupp, Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost Civilizations |